There is a significant overrepresentation of Indigenous children in child welfare systems in all of North America.

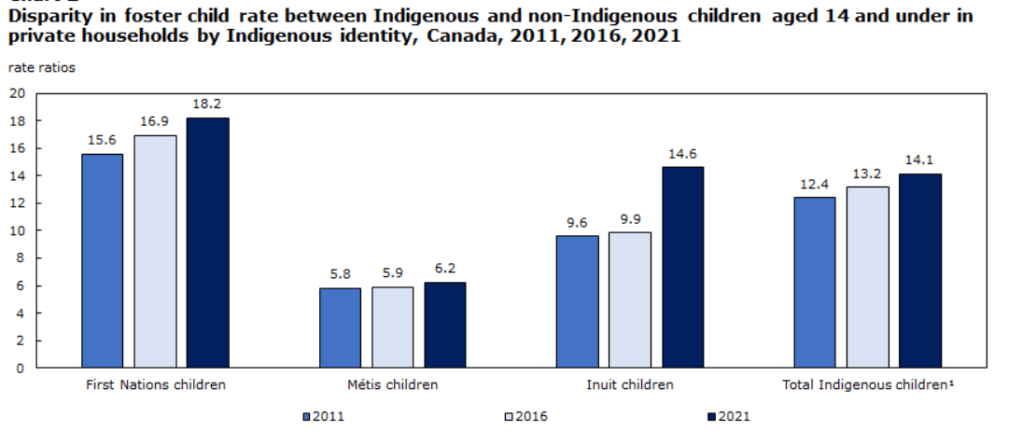

In 2021 in Canada, the total Indigenous foster child rate was 14.1 times greater than the non-Indigenous foster child rate, with some differences between First Nations, Inuit and Métis children.

In the past decade, there was an increase in the overrepresentation of Indigenous children among foster children in private households, with Indigenous children accounting for 47.8% of all foster children in 2011, to accounting for 53.7% in 2021.

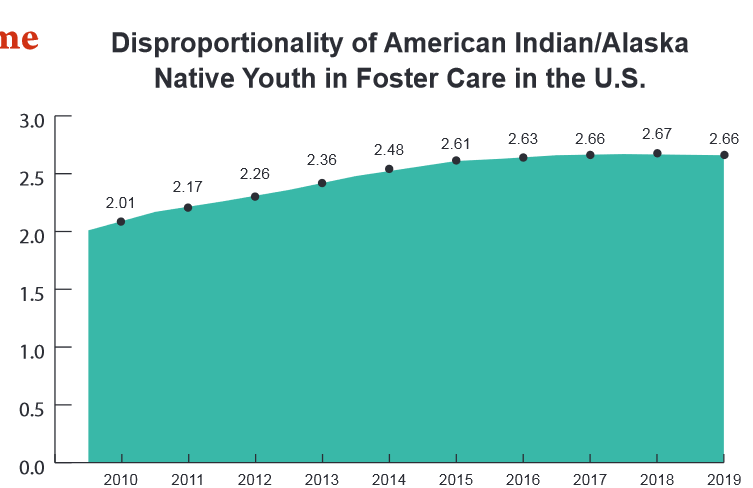

In 2019 in the US, American Indian and Alaska Native children were overrepresented in state foster care at a rate 2.66 times greater than their proportion in the general population.

Additionally, cases of concern of abuse are more often investigated and substantiated for Indigenous children compared to white children. These numbers are very high and quite concerning, and there is also quite some history tied to why this is currently the case.

History

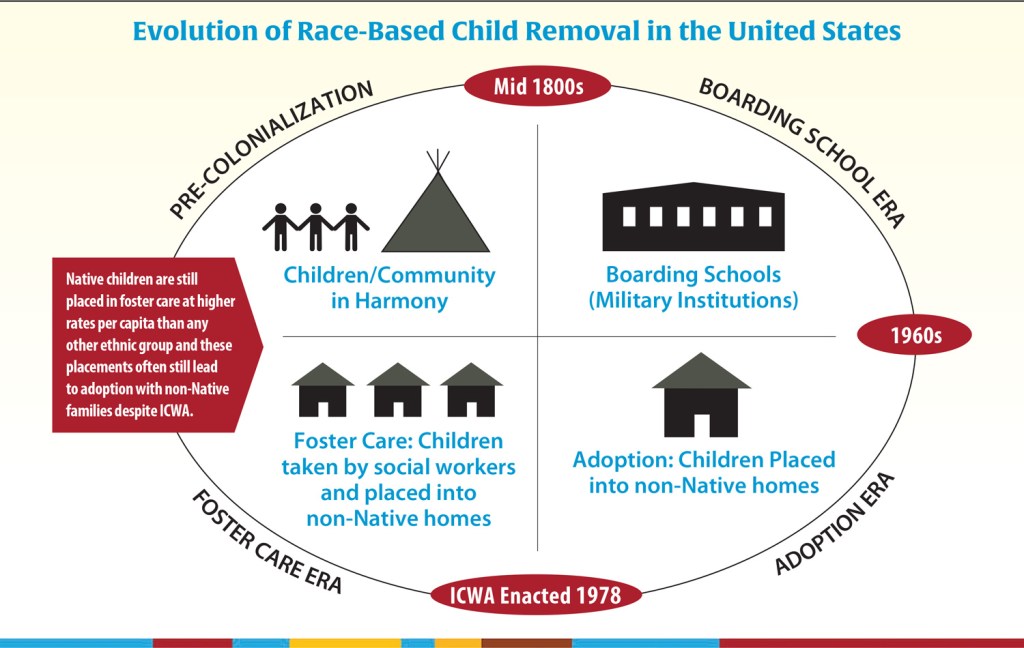

– In 1958 the Bureau of Indian Affairs created the Indian Adoption Project, administered by the Child Welfare League of America, to promote adoption of Indigenous children from 16 Western states by white families in the East.

– The purpose of this act was to allow children to escape their reservations and be raised in middle and upper-class families, where they would learn morality and values, would gain resources that would provide good education, which would then give them access to the American Dream.

– Margaret Jacobs, non-Native author of a book on forced Indian adoption: “when you removed a child and put them in a non-Indian family, they wouldn’t be getting to know other Indian people as they would in boarding school, they would hopefully be raised in a middle-class family. And so the idea was that they would be fully assimilated, and at no cost to the government”

– By 1972, between 25% and 35% of American Indian children had been removed from their homes. About 85% of these were adopted by non-Indigenous families. The ages of the children ranged largely between birth and 11 years old, and almost half that were placed in adoptive families were under a year old.

– The adoption of children was even advertised, and it targeted white families by claiming that not to adopt would be choosing to leave Indigenous children with no chance of survival, suggesting that their own families would not be able to provide for them, so it’s up to white families to help.

– The project enlisted social workers to visit reservations and convince parents to sign away parental rights. Some social workers also used coercive means to take the children, for example, by threatening the parents to terminate their welfare payments if they opposed it.

– A form developed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which was called ‘authorization of an infant’ did not say anything about adoption, losing one’s child, or giving up rights to one’s child. So, legal language was a tool used to manipulate families into signing their children over.

– In the 1970s, Indigenous activists and allies criticized the Indian Adoption Project, and called it out for being yet another genocidal policy to destroy the cultures of Indigenous communities.

– In one of the hearings in 1974, director of the Association on American Indian Affairs said that “a survey of North Dakota tribes indicated that of all the children that were removed from that tribe, only 1% were for physical abuse. About 99% were taken on the basis of such vague standards as deprivation, neglect, taken because their homes were thought to be too poverty stricken to support their children”.

– So, between 1974 and 1977, Congress carried our hearings into adoption processes.

– In 1978 the Indian Child Welfare Act was introduced.

– Approx. from 1951 until the 1980s, the Sixties Scoop referred to the forced removal of Indigenous children from their families. This began in 1951, when changes to the Indian Act gave the provincial government authority over Indigenous child welfare.

– Social workers did not have any training in dealing with Indigenous communities, so they had no idea about their culture and history, and what they viewed as proper care was based on Western values. For example, social workers who saw families following a traditional Aboriginal diet that consists of dried game, fish, and berries, or when they saw that their kitchen set-up did not look like the typical Western one, the social workers assumed that the children were not being provided for.

– By the mid-1960s, the number of Indigenous children in the child welfare system in some provinces was over 50 times more than it had been in the beginning of the 1950s. – By the 1970s, around 1 in 3 children in care were Indigenous, and around 70% of those children were placed in non-Indigenous homes. In most of these homes, any knowledge of their heritage was denied, and sometimes the adoptive parents would even tell their children that they’re French or Italian.

– Even those who suspected about their true heritage couldn’t confirm it, because the government policy at the time did not allow birth records to be opened unless both the child and parents consented.

– Even worse, Indigenous children were even sent overseas, to countries such as the United Kingdom, Germany, India, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Botswana.

– In 1985, Judge Edwin Kimelman released No Quiet Place: Review Committee on Indian and Metis Adoptions and Placements, which was a report on Indigenous adoption, in which he stated that “cultural genocide has taken place in a systemic, routine manner”, and emphasized that Indigenous children from Canada were placed in adoptive American families, calling it a policy of wholesale exportation.

– During the 1980s, provinces amended their adoption laws to prioritize Indigenous children adoption into Indigenous families.

– In 1990, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada created the First Nations Child and Family Services program, which transferred administration of child and family services from the province to the local band, making it so bands can run their own social service.

– Of course, the forced removal of children and placement in non-Indigenous families left major impacts on the children growing up – loss of cultural identity and loss of heritage, disconnection from their cultures and families. Many survivors also endured physical, emotional and sexual abuse. Addictions, self-harm, suicide.

– One survivor, Sandy White Hawk, recalls that “my adoptive mother constantly reminded me that no matter what I did, I came from a pagan race whose only hope for redemption was to assimilate to white culture”.

– In 2017, Canada’s government reached a settlement agreement to compensate survivors of the Sixties Scoop for the loss of their culture, language, and identity.

– Until 2019, claims for compensation could be made by those who are First Nations, Inuit or Metis, those who were taken from their home during the Sixties Scoop, and those who were placed in non-Indigenous homes.

– Part of the settlement included 50 million dollars to establish an independent Indigenous healing foundation to provide culturally appropriate counseling for survivors. The foundation was developed after sessions with survivors were held in 10 locations across Canada, where they shared their experiences and decided on what the foundation should do, who should govern it, and what it should be called.

Current situation

One of the main issues that is present today is the severe underfunding of child welfare, social and health services. Additionally, in recent years more research has been done to look for the reasons behind the continuous overrepresentation of Indigenous children in the system.

One of the main driving forces behind this overrepresentation are cases involving concerns about neglect, with the rate of neglect investigations involving First Nations children being six times greater than the rate for non-Aboriginal children in 2008 in Canada.

An article by Caldwell and Sinha from 2020, investigated the concept of neglect, and how it has affected the overrepresentation of Indigenous children in the child welfare system in Canada.

One of the main points from this article is the fact that the term ‘neglect’ is quite vague, and often not properly described in child welfare legislation. The most common definition is often related to a lack of material needs and physical safety, and ignoring the child’s relational needs. Additionally, a lot of legislation mandates the child welfare system to already intervene in situations in which a child is at risk of maltreatment or neglect, even if there is no allegation or suspicion of it yet. This just further complicates the judgment and concept of neglect. The authors described neglect as ‘an act of omission’, something is lacking from the child’s life, but this makes it a rather intangible concept and leads to many social workers being able to have a very subjective view of what neglect or risk of neglect looks like.

On top of this difficulty in conceptualization, many child welfare service workers focus their investigations on the primary caregiver, most often the parent, and whether they are able to provide the needs of the child. This ignores the presence of the larger family or community who are often involved in Indigenous childrens’ lives, and marginalizes Indigenous notions of family life.

Lastly, structural factors such as poverty and unstable housing have been associated with reported cases of neglect in First Nations families. Based on the history of the treatment of Indigenous communities by the Canadian government, these factors have resulted from settler colonial policies. The following quote from the article sums it up nicely:

“…the individually focused, risk-centered approach reflected in legislated and operational understandings of child neglect obfuscate the connections among settler colonialism, intergenerational trauma, structural factors, and neglect. It reduces the intergenerational trauma and structural contexts systematically resulting from settler colonial policies to a collection of caregiver and household risk factors, obscuring the ongoing impact of these policies on the lives of Indigenous families.”

An article by Leckey et al. from 2021, investigated the experience of Indigenous parents with the child welfare system through the perceptions of some lawyers, social workers and judges. Some highlights of the issues and struggles that they found many Indigenous parents face when dealing with the child welfare system:

- There is generally a lot of widespread mistrust among Indigenous families and parents of the child welfare system. Those engaged with the system often feel like their experiences, perspectives and needs are given less credit than those of the state’s social workers.

- Indigenous families often face language troubles, as interpreters are often lacking, and some judges do not allow time to wait for their availability, leading to decision-making without proper communication from the Indigenous parents’ side. This goes hand in hand with the fact that there are many barriers for Indigenous parents to participate in court. They are often not adequately supported in dealing with the legal system of child welfare, as they often do not understand the functioning of the judicial system.

- Lastly, there is a lot of epistemic injustice present, Indigenous parents’ knowledge and statements receive less acknowledgement than their fair weight, and social workers and lawyers tend to speak on behalf of the parents, which has also harmed them in the final decision.

Recent news

- In 2023, the US Supreme Court ruled in favor of the ICWA to be upheld, despite many challenges.

https://ictnews.org/news/unpacking-the-historic-brackeen-v-haaland-decision

- Indian Child Welfare Act faces another constitutional challenge, a year after the Supreme Court ruling.

https://ictnews.org/news/indian-child-welfare-act-faces-another-constitutional-challenge

- Reunifying Native families after foster care.

- Indian Child Welfare Act grants awarded for off-reservation programs.

- Supreme Court of Canada Ruling on an Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth, and families.

References

Aboriginal Legal Aid in BC. (n.d.). Sixties Scoop | Aboriginal Legal Aid in BC. Aboriginal.legalaid.bc.ca. https://aboriginal.legalaid.bc.ca/issues/sixties-scoop

Adoptee, D. (n.d.). #Flipthescript. http://www.thelostdaughters.com/p/flipthescript.html

Alvarez, B. (2023, November 15). Native American History: Documentaries On American Indian Boarding…. PBS. https://www.pbs.org/articles/native-american-history-documentaries-about-residential-schools-and-forced-adoptions

Baswan, M., & Yenilmez, S. (n.d.). The Sixties Scoop. The Indigenous Foundation. https://www.theindigenousfoundation.org/articles/the-sixties-scoop

Caldwell, J., & Sinha, V. (2020). (Re) Conceptualizing Neglect: Considering the overrepresentation of Indigenous children in child welfare systems in Canada. Child Indicators Research, 13(2), 481–512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09676-w

CBC. (2018, March 21). Saskatchewan’s Adopt Indian Métis program. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/findingcleo/saskatchewan-s-adopt-indian-m%C3%A9tis-program-1.4555441

Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. (2024, April 18). Indigenous foster children living in private households: Rates and sociodemographic characteristics of foster children and their households. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/41-20-0002/412000022024001-eng.htm

Hanson, E. (2009). Sixties Scoop. Indigenous Foundations; University of British Columbia. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/sixties_scoop/

Harness, S. D. (2022, May 12). Voices of Indian Adoption – Bill of Health. Blog.petrieflom.law.harvard.edu. https://blog.petrieflom.law.harvard.edu/2022/05/12/voices-of-indian-adoption/

Herman, E. (2012). Adoption History: Indian Adoption Project. Pages.uoregon.edu. https://pages.uoregon.edu/adoption/topics/IAP.html

Indian Affairs. (n.d.). Indian Adoption Project Increases Momentum | Indian Affairs. http://Www.bia.gov. https://www.bia.gov/as-ia/opa/online-press-release/indian-adoption-project-increases-momentum

Leckey, R., Schmieder-Gropen, R., Nnebe, C., & Cloutier, M. (2021). Indigenous parents and child welfare: Mistrust, epistemic injustice, and training. Social & Legal Studies, 31(4), 559–579. https://doi.org/10.1177/09646639211041476

Maclean’s. (2017, November 29). Why Indigenous children are overrepresented in Canada’s foster care system [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MBLCd7yle8g

Marie Spears, N. (2024, March 9). Indian Child Welfare Act Faces Another Constitutional Challenge. Indian Country Today. Retrieved April 30, 2024, from https://ictnews.org/news/indian-child-welfare-act-faces-another-constitutional-challenge

MPR News. (2017, February 13). A look at the lasting effects of forced adoption. MPR News. https://www.mprnews.org/story/2017/02/13/cultural-impact-of-the-indian-adoption-project-still-felt-today

NABS. (2020, October 30). Indian Boarding Schools: The First Indian Child Welfare Policy in the U.S. The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. https://boardingschoolhealing.org/indian-boarding-schools-the-first-indian-child-welfare-policy-in-the-u-s/

National Adoption Month – Child Welfare Information Gateway. (n.d.). https://adoptionmonth.childwelfare.gov/topics/adoption/nam/#:~:text=November%20Is%20National%20Adoption%20Month&text=Learn%20more%20about%20this%20year’s,points%20of%20connection%20with%20youth.

National Indian Child Welfare Association. (2021). Disproportionality in Child Welfare. In National Indian Child Welfare Association. https://www.nicwa.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/NICWA_11_2021-Disproportionality-Fact-Sheet.pdf

Palmiste, C. (2011). From the Indian Adoption Project to the Indian Child Welfare Act: the resistance of Native American communities. https://hal.univ-antilles.fr/hal-01768178/document

Spears, N. M. (2023, June 21). ‘A Place of Calm:’ Indian Child Welfare Expert Unpacks the Historic Brackeen V. Haaland Decision. The Imprint.

Sixties Scoop Settlement. (n.d.). CLASS ACTION – Sixties Scoop Settlement. Sixtiesscoopsettlement.info. https://sixtiesscoopsettlement.info/

The Indian Child Welfare Act. (2014). Understanding The ICWA | Indian Child Welfare Act Law Center. The Indian Child Welfare Act. https://www.icwlc.org/education-hub/understanding-the-icwa/

Trocmé, N., Knoke, D., & Blackstock, C. (2004). Pathways to the overrepresentation of Aboriginal children in Canada’s child welfare system. the Social Service Review/Social Service Review, 78(4), 577–600. https://doi.org/10.1086/424545

Wild, E. (2023, June 17). Here’S What Indian Country and Government Leaders Are Saying About the Haaland V. Brackeen Ruling. Native News Online.

Upstander Project. (2024). Indian Adoption Project. Upstander Project. https://upstanderproject.org/learn/guides-and-resources/first-light/indian-adoption-project

You’re Breaking up: Adoptive Couple V. Baby Girl #ICWA. (n.d.). http://blog.americanindianadoptees.com/p/you.html

Resources:

Leave a comment