Clothing played a pivotal role in Canadian residential schools, where it served as a potent tool of assimilation. Clothing was forcibly replaced upon arrival and symbolized the imposition of Western values and the erasure of Indigenous identity. Uniforms, devoid of personal choice, reflected an agenda aimed at aligning children with Western notions of civilization. To grasp the profound impact of clothing, we must acknowledge its intimate link to selfhood, as it delineates boundaries between individuals and society. Shawkay Ottmann (2020), “the body and dress are intertwined,” underscores how attire embodies personhood and identity from an early age. Through our analysis, we reveal how clothing functions as more than mere garments, serving as a conduit for cultural representation and identity formation.

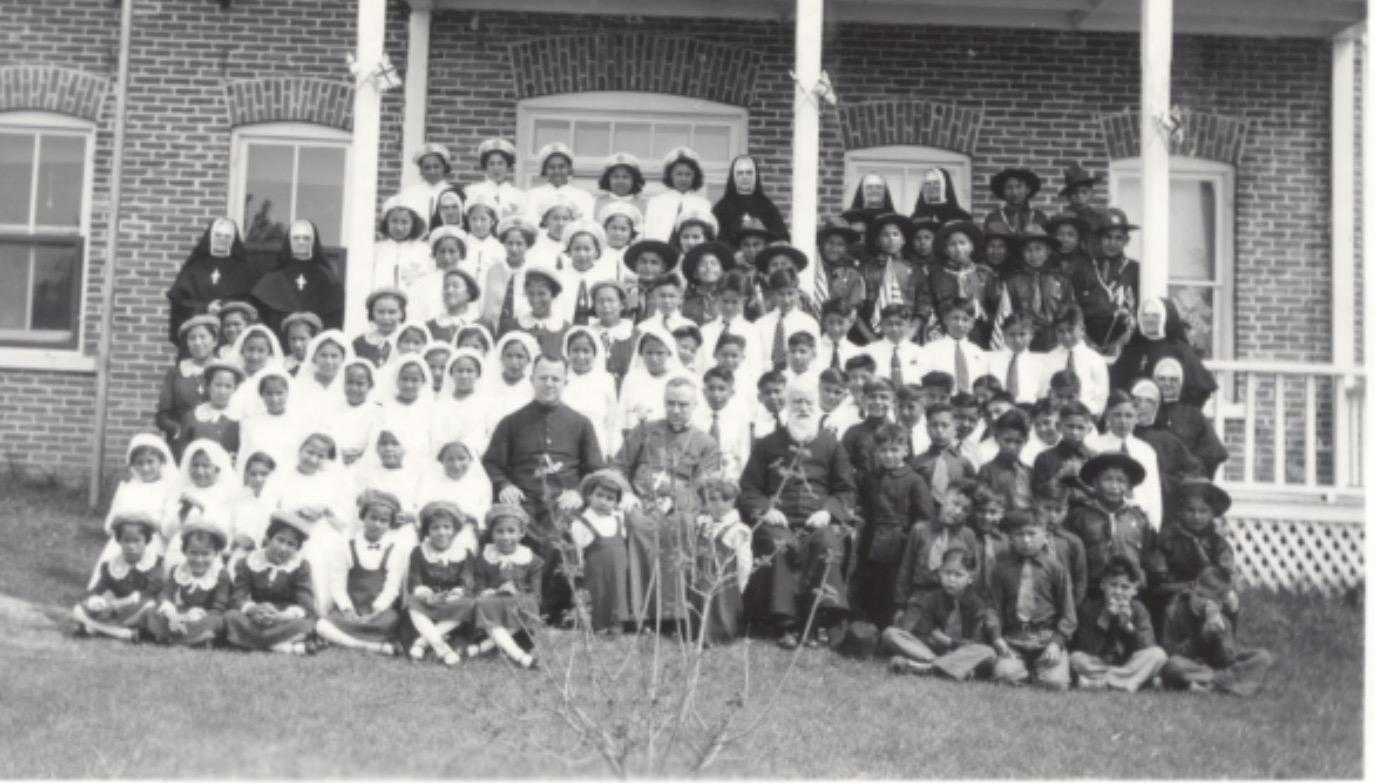

To comprehend the impact of residential schools on clothing, it’s crucial to grasp the attributes of traditional Indigenous attire. Through powerful imagery, we witness the transformation brought by this assimilationist agenda. Traditional clothing reflects Indigenous values and worldviews deeply rooted in nature. Shawkay Ottmann elucidates that Indigenous ontologies vary among nations but share commonalities, such as the animacy of nature and the equal positioning of humanity within the cosmos. Clothing serves as a conduit for maintaining balance with the natural world and honoring the sacrifices of animals. Well-made garments signify respect for the animals, ensuring continued favor in providing for human needs. This reverence extends to the practical and aesthetic aspects of clothing, embodying respect and connection to the community and the natural environment. Moreover, clothing represents a connection to familial lineage, particularly through the roles of women in garment creation. Elements like headdresses and strips symbolize a deeper relationship with the elements and ancestral traditions. While Western ideology emphasizes that “clothes make the man,” Indigenous belief holds that clothing fosters relationships. Thus, the imposition of Western dress in residential schools was not merely about attire but a profound alteration of Indigenous ontologies and epistemologies, aimed at “civilizing” Indigenous children.

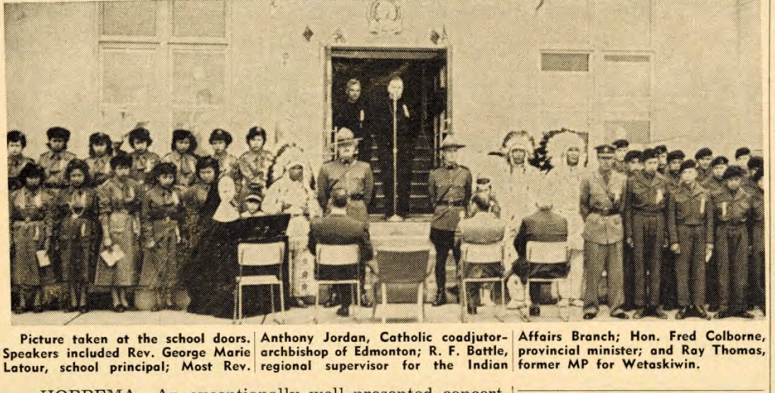

Within the confines of residential schools, where uniforms were the norm, instances of cultural appropriation emerged as a poignant manifestation of assimilationist policies. Traditional Indigenous clothing resurfaced within these institutions, not as cherished attire but as “costumes,” marking a troubling practice of erasure and degradation. The reappropriation of Indigenous clothing as costumes stripped away their original cultural significance, relegating them to symbols of mockery rather than reverence. This act not only undermined the children’s sense of identity and belonging but also reinforced power dynamics within the school system, often subjecting them to humiliation. Photographic evidence depicts children adorned in Indigenous attire, labeled as costumes for occasions like Halloween or carnival, further perpetuating the erasure of Indigenous identities. This observation underscores the systematic attempt to assimilate Indigenous children into Western standards, disregarding their cultural heritage and reinforcing the dominant power structures within the residential school system. Ultimately, the prevalence of cultural appropriation highlights the deeply damaging effects of erasing Indigenous identities, perpetuated throughout Canadian history.

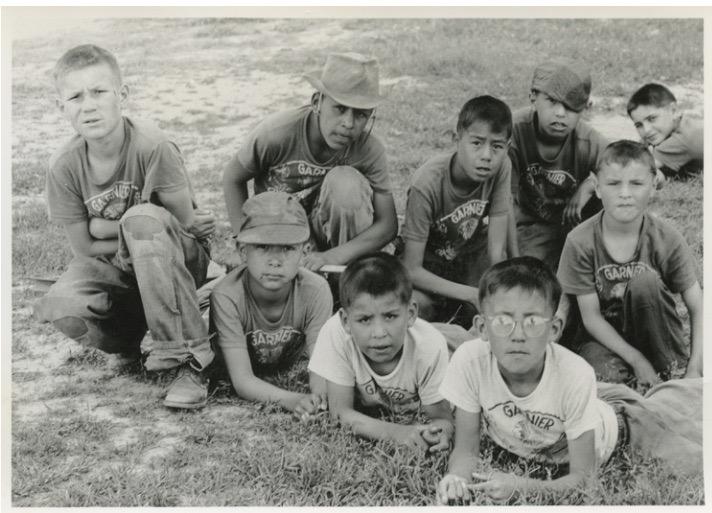

A critical aspect of assimilation within Canadian residential schools was the imposition of Western gender norms through clothing, imbued with symbolic meanings and roles. Examining a plethora of images depicting uniforms for boys and girls reveals distinct patterns reinforcing gender roles and expectations. For boys, loose-fitting attire predominates, reflecting the assumption that outdoor activities necessitate freedom of movement. Photographs depicting boys engaged in sports or farm work underscore this notion, contrasting with the more static images of girls indoors, engaged in tasks like sewing and cooking. Furthermore, boys exhibit a greater variety in clothing options, suggesting a broader range of activities and less uniformity compared to girls. Darker hues prevail for boys, signifying practicality, while white emerges as a recurring color for girls, symbolizing purity and innocence. The prevalence of white dresses for girls, even outside of religious contexts, underscores the deep-rooted symbolism associated with femininity and virtue. Notably, the wearing of veils by girls, beyond religious contexts, carries symbolic significance, representing chastity, obedience, and hidden knowledge. Unlike the utilitarian use of hats by boys, the veiling of girls’ hair in class pictures conveys a disciplinary tone, reinforcing gendered roles and expectations. In essence, the gendered clothing and symbolism within residential schools underscore the systematic imposition of Western gender norms, perpetuating traditional roles and expectations while erasing Indigenous ways of being and dressing.

Photograph of senior girls confirmation and girls activities, (1940-1965)

Photograph of boys activities and boys doing farm work (1940-1965)

Hair holds profound spiritual and cultural significance for Indigenous tribes, symbolizing strength, power, and individual and societal identity. However, within the confines of Canadian residential schools, this significance was systematically undermined and stripped away. Boys were prohibited from growing long hair, echoing European notions of morality and discipline, while girls were constrained to specific hair lengths, severing their connection to spirituality and maternal lineage. Punishment for runaways often included shaving off hair, inflicting lasting humiliation and erasing personal autonomy. The visual representation of this cultural clash remains potent, echoing through images, toys, and gifts exchanged in these institutions. The forced alteration of hair reflects a broader pattern of cultural suppression and dehumanization within Canadian residential schools.

Clothing served as a pivotal tool in the implementation of civilizational theories within Canadian residential schools, where Western attire was imposed as a marker of civilization. This tactic aimed to disorient Indigenous children from their established understanding of dress, positioning European attire as the standard of civility. The traumatic experience of stripping children of their clothing, particularly through hair cutting, instilled a sense of shame and inferiority, reinforcing the belief that their Indigenous identity was inherently dirty or uncivilized. Testimonies reveal a profound sense of loss as children were forcibly separated from their community connections. Photographs depicting children in uniforms on picture day were used to promote the schools, yet these clothes often failed to meet basic comfort or sizing standards due to budget constraints. Western-style uniforms, with uncomfortable high collars and stiff shirts, exacerbated the physical discomfort experienced by students. Uniforms served as a means of punishment and control, with students subjected to humiliation through ragged clothing or dunce caps. Additionally, strict dress codes imposed uniformity and erased individual and cultural identities, reinforcing Western dominance within the schools. Research highlights the significant influence of uniforms in shaping behavior and promoting Western ideals of civilization and power. Ultimately, clothing became a potent tool in erasing Indigenous identity and enforcing assimilation within Canadian residential schools.

References

Ottmann, S. (2020). Indigenous dress theory in Canadian residential schools. Fashion Studies, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.38055/fs030105

Robinson, A. (2018, 25 juni). Indigenous regalia in Canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/indigenous-regalia-in-canada

Hilleary, C. (2018, 10 januari). Native Americans, Canada’s First Peoples, Fight to Keep Long Hair. Voice Of America. https://www.voanews.com/a/native-americans-canadas-first-peoples-fight-to-keep-hair-long/4199671.html

Jaffe, E. (2001). Online Symbolism Dictionary. Fantasy and Science Fiction. https://public.websites.umich.edu/~umfandsf/symbolismproject/symbolism.html/index.html

Godey’s magazine and Lady’s Book. (1849). Godey’s magazine and Lady’s Book. New York Public Library.

Standing Bear, L. (1975). My People, the Sioux. Google Books. https://books.google.nl/books?id=x6PkqlYly8kC&redir_esc=y

Leave a comment